Celebrated Okinawan writer Oshiro Tatsuhiro died last month, on 27th October 2020, at the age of 95. His demise reminded me of an article I wrote a few years ago on Okinawan literature that was published in the magazine Kansai Time Out. The article mentions Oshiro but focuses mainly on another Okinawan writer, Medoruma Shun. It may as well go in the Features Archive, so here it is below.

Healing Islands?

John Potter reads Okinawan writers who address the issues

The pervading theme of most modern writing in Okinawa and the Ryukyus is the island people’s identity in the wake of the Second World War. More than a third of the population was killed during the Battle of Okinawa in 1945, when the islands were sacrificed by the Japanese in an attempt to delay an invasion of the mainland. After reversion of the islands to Japan, the Okinawans’ situation has remained poor in comparison to the rest of Japan. The large amount of money given to the Ryukyus by the United States after the war was not to help Okinawans but to expand and sustain the American military. This situation continues today with the collusion of the Japanese government and it is well known that over 20% of the main island is still occupied by the American military forces. At present, out of all of Japan’s 47 prefectures, Okinawa has the nation’s lowest per capita income and its highest unemployment. It also has the highest divorce rate, and the lowest percentage of students entering university. Okinawans have to live daily with the issue of the American occupation and the massive military presence. Not surprisingly, many of today’s writers, such as Medoruma Shun, address these problems both in fiction and essays.

The islands were, of course, an independent kingdom for many years and the Ryukyu Kingdom was finally abolished after another invasion – by the Japanese this time – in 1879. As Okinawan literature developed after the Japanese invasion, many works of literature were derived from kumi-odori (Ryukyuan dance-drama). However, Okinawans were now having to write in standard Japanese and were developing a modern literature of their own, mainly centred around the novel and poetry. The Second World War brought an end to all literary activity, but after the war writers began to appear whose concerns were very much linked to the American occupation. The literature produced under U.S. rule was mainly written by war survivors. After reversion of the islands to Japan in 1972, a younger generation of writers appeared who had not directly experienced the war.

In the 1950s, there arose a new young generation of writers and a literary movement known as “Literature of Ryudai” which was started by students from the University of the Ryukyus. They published a radical magazine called Ryudai bungaku which insisted on incorporating political and social, as well as literary, issues. They were united in resistance to the military rule of the islands, but their movement was eventually suppressed. Then the 1960s saw the start of the literary magazine Shin Okinawa Bungaku (New Okinawan Literature) and various literary awards were instigated. During this period, the writer Oshiro Tatsuhiro (born 1925) became the first Okinawan to win the prestigious Akutagawa Prize for his novella “Cocktail Party”, which deals with the injustices of the American occupation. The story includes the rape of an Okinawan girl by an American soldier. This has a new relevance today in light of the notorious rape of a 12-year-old by three American servicemen on Okinawa in September 1995. Following on from this, there has been a blossoming of Okinawan literature right up until the present.

Among the new generation of writers born since the war is the poet Takara Ben, who in addition to writing poetry is involved in political activism and social criticism. He is particularly interested in the experiences of indigenous minorities such as the Okinawans and Ainu, and is also an advocate of Ryukyuan independence. Two of the best known contemporary novelists are Matayoshi Eiki and Medoruma Shun. In 1996, Matayoshi won the Akutagawa Prize for his novella “Buta no Mukui” (“The Pig’s Revenge”), later made into a film. The following year another Okinawan won the prize when it was awarded to Medoruma Shun for his story “Suiteki” (“Droplets”). These awards signalled the arrival of Okinawan literature as a serious force, if it wasn’t already known to most Japanese.

There has also been an increase in the number of female Okinawan writers and especially worthy of mention are Yoshida Sueko and Yamanoha Nobuko, who were both born in the 1940s. Yoshida’s story “Kamaara Shinju” (“Love Suicide at Kamaara”) won the Shin Okinawa Bungaku literary prize in 1984 and is about the plight of the prostitute in Okinawa. Yamanoha, meanwhile, writes about contemporary Okinawan life in relation to nature and indigenous religious beliefs. Despite the success and vitality of Okinawan literature it is less commercially viable in Japan than the higher profile performing arts such as the thriving Okinawan music scene, and writers are rarely able to survive on the proceeds of their book sales.

The rather reclusive Medoruma Shun worked as a schoolteacher on Miyako Island and is now a writer on the main island of Okinawa, where he was born in Nakijin in 1960. Medoruma – his name is a pseudonym and he has requested that his real name not be used – graduated from the University of the Ryukyus. Much of his literary work is published in the form of short stories and novellas, and his essays are usually written in Okinawan hogen (dialect). In 2000, he won the Kawabata Yasunari literary award for his story “Mabuigumi” and in 2004 another of his stories, “Fuon”, was made into a film. His latest book, published last year, is “Niji no tori” (“Rainbow Bird”). He says, “When I write my stories, I have a great influence from things I have heard about the Battle of Okinawa from my parents and grandparents, plus my own experience after the war.” He has also addressed the subject of independence: “When we talk about Okinawan independence, I find that there are some young people growing up who think we cannot really rely on mainland Japan because as long as we rely on it, we cannot have a good future.”

“I still think the majority of Japanese people look down on Okinawans, or they are not interested in them at all. For example, the image of Okinawan men in the NHK television drama series Churasan is of someone who hates work and loves alcohol. That kind of image gives people the idea that Okinawa is no good. On the surface, people think there’s an Okinawan boom going on but in fact there is discrimination underneath which is still strong. Frankly speaking, I find it painful to walk along Kokusai-dori in Naha which is full of Yamatonchu (Japanese) tourists, so maybe I have some prejudice against them too.”

In his recent book of essays Okinawa Sengo Zeronen, Medoruma aportions blame for the current situation in Okinawa not just to the Japanese and American governments, but also to Okinawan people. Since the protests following the 1995 rape incident, Okinawans have been encouraged to forget terrible problems such as military occupation and the environmental degradation of their islands, and instead to look on the bright side. It is no coincidence, he says, that Churasan presented only the happy-go-lucky image of Okinawa – the government was quick to ensure that the 2000 G8 Summit was largely held in Okinawa; and a picture of Shuri castle was soon to be included on the new 2,000 yen note. Financial support is frequently promised to the islands in return for their compliance in government schemes which more often benefit only the mainland. Okinawa is seen by mainland Japanese as a “healing” island. For Medoruma, this goes beyond anger and makes him feel only sadness.

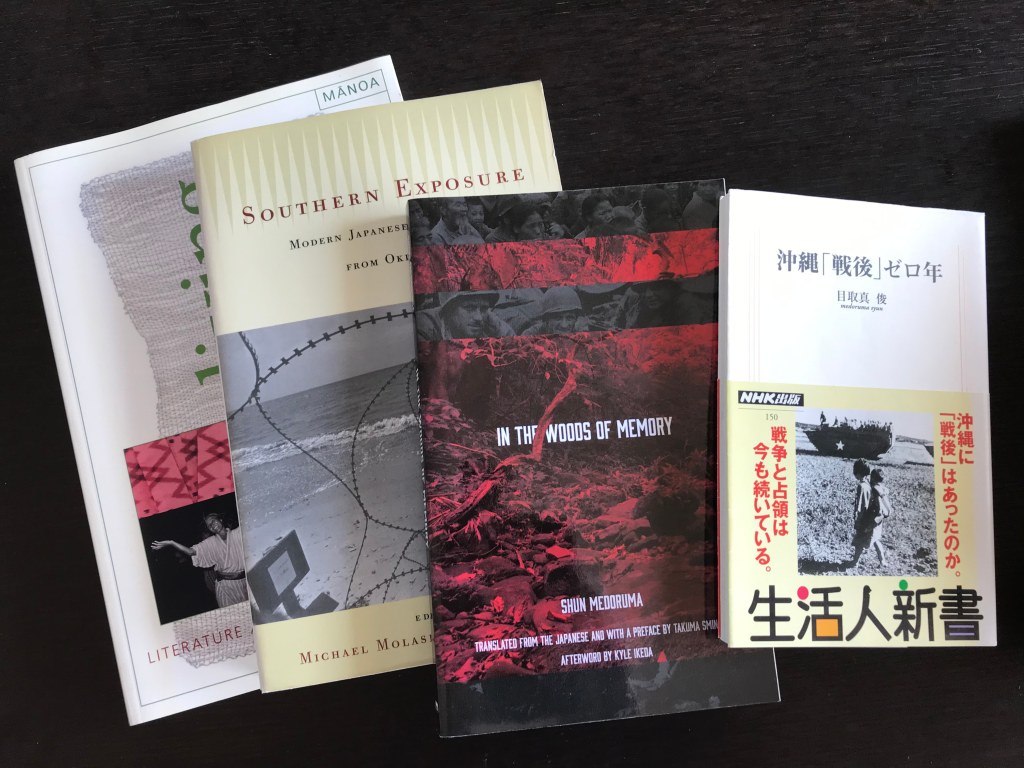

For more, see Southern Exposure: Modern Japanese Literature from Okinawa (University of Hawaii Press, 2000).

(Kansai Time Out, March 2007)

For more Okinawan literature in English translation see also Living Spirit: Literature and Resurgence in Okinawa (University of Hawaii Press, 2011) and In the Woods of Memory by Medoruma Shun (Stone Bridge Press, 2017).